Photo: Laurent Wright

Paola Pivi: wandering through a career driven by bold decisions

Conversation with |

Patrizia and Paola discover details that link their stories before they ever met while talking about the inspiration behind her work and her origins as an artist.

“OK, you are better than me, so what?”, 2013, Perrotin, New York. Photo: Guillaume Zicarelli. Courtesy of the Artist and Perrotin

Patrizia and Paola discover details that link their stories before they ever met while talking about the inspiration behind her work and her origins as an artist.

World-renowned artist Paola Pivi has a casual conversation with Moroso’s Art Director Patrizia Moroso in which they retrace together the steps that took her from an analytical chemical engineering student to the flamboyant creator that she is today.

Paola’s beginnings are characterised by unexpected twists and turns that allowed her to express her talent and passion, so much so that along the way they discover that their stories came into contact earlier than they thought. A friend from Patrizia’s time in university might have helped to sway destiny just enough to kindle a spark of curiosity in Paola. A chance encounter at the library ignited a fascination for the world of art. Opening the right door at the right time inspired further curiosity and wonder, leading to a professional career as a world-renowned artist.

Sculpture, performance and photography were just some of the media explored by her in the course of her decades-long career, and now her flamboyance meets with More-So in a collaboration: Milano.

Works × More-So:

Exhange between Patrizia and Paola

Paola and Patrizia take some time from their busy schedules to talk about how she started out as an artist and how her exploration of the various media with which to express herself and the point in time in which her story connects with Patrizia.

Exhange between Patrizia and Paola

Paola and Patrizia take some time from their busy schedules to talk about how she started out as an artist and how her exploration of the various media with which to express herself and the point in time in which her story connects with Patrizia.

I would like to ask you about your beginnings; did you, immediately start attending the Accademia delle Belle Arti as a young Milanese woman, or was it not like that?

I find my beginnings to have been adorable because I was studying chemical nuclear engineering.

I find that amazing!

At that point I had never really interacted with art, not until a very late age, at about 22 or 23 years old. Until that age art was basically the replica my grandfather had hanging on a wall. Luce [Luce Balzarini], my project manager with whom I’ve been friends since we were 14 years old, used to buy big art books, and I used to think: “She must be crazy to buy those massive art books. You could buy shoes with that money!” At that time art was a distant thing for me, even though I was already an artist. In truth, it exists within other people close to me in my family, but it was more or less rejected.

You didn’t want to recognise it? In some way you dedicated yourself to an incredibly rational subject, but ultimately a creative one, like chemical nuclear engineering, which I honestly can’t even begin to understand.

Actually, there wasn’t much if any creativity there. I wasn’t rejecting art, as much as the system in which I was immersed was rejecting it. I must say, when I was studying engineering, I wasn’t lucky enough to meet any creative engineers.

If that had been the case, would you have followed that path?

Yes. I took the last quantum mechanics exam, and the professor gave me a 30 plus lode and then asked me: “Do you want to be my assistant?” And I told him: “I would, but about 5 minutes after you sign these papers, I’m going to drop out from engineering and start attending the art academy.” (In the Italian University scoring system, the grade is given out of a 30-point total, then the professors can demonstrate further appreciation for a student’s work with a “lode” or praise in Italian).

You had already made up your mind.

I had already made up my mind. If I’d had an opportunity like this, maybe 2 or 3 years earlier, my life could have been different, but it had never, ever, ever, ever happened. Actually, there was a professor that everyone feared, strict and grumpy: Quartapelle. When I took his exam, he gave me a 28 and asked me: “What are you doing here? You must leave. You are not good enough”.

Oh, just like that?

Yes, he very rarely gave a score higher than 18. And so, it happened. When I left engineering, I didn’t suspect in the slightest that I was going to become an artist. I enrolled in the arts academy, which is something one can do from passion, with no work-related implications. As a matter of passion because studying was logical, if not automatic. I was lucky enough to be surrounded by a family in which studying was normal, and so I was going to study something that was beginning to fascinate me, on a whim.

Perhaps as a way to slowly distance yourself from engineering with something that was its polar opposite and was a passion that you could have spent some time studying.

Basically, what happened next is that I attended one of Professor Garutti’s classes, as in: one day I opened the door to Garutti’s, Alberto Garutti’s, classroom, I got to see him teach and the whole situation was simply fascinating. For the next 3 years I religiously attended his lessons. We used to meet up at 9 a.m. and leave at 2 or 3 in the afternoon. I did it each and every, every, every single day of my life for 2 or 3 years.

At the Brera Academy?

Yes, and by the end of the first year he had already organised an exhibition featuring us students with Giacinto Di Pietrantonio, the art history professor. Garutti instructed us to follow his course saying: “If you want to attend my course, either you take art history with Giacinto or it’s just quicker if you leave.” And so, he and Giacinto had organised the exhibition in none other than Via Farini, giving me my first exhibition.

Such an important achievement so soon! This really is a beautiful story. It often happens that the greatest individuals in a field started out doing something completely different. It’s sort of like Destiny’s call that guides people fated to do something towards that thing at a certain point in their lives. Truly beautiful. I might not know about your earliest work, but when I finally got to know about you and met you, you had just won the Leone d’oro at the Biennale in Venice, right? If I remember correctly, it was the same year or the year after you won it with a performance, so initially your art included more performances? How was this winning project for Venezia born?

In Venice I installed the flipped aeroplane, so it’s a sculpture with a performance ingredient but it was an installation. I didn’t win alone, there were 5 of us women that made up the Italian pavilion because that year Harald Szeeman didn’t want to make it. However, all the Italians started complaining like mad and he said: “Well then, you guys complain so much that I’ll make the Italian pavilion. It will comprise the 5 Italian women that I have already selected.” Our works were scattered around his big exhibition and, we represented the Italian pavilion just like that in abstract fashion. There wasn’t an Italian pavilion per se, but we were all scattered in the international exhibition. We won because our pieces were beautiful.

What year was the Donkey on a Boat from?

That was from the 2003 Biennale, the plane was from the ’99 one.

Oh I see; the plane came before! I must have confused the 2003 one with the other one.

No worries. In 2003 at the Biennale curated by Francesco Bonami, I exhibited the photo of the donkey on a boat on a big billboard hanging from a building close to the Arsenale. More than a building, it was like a strange construction with a wide flat wall facing the canal on which I put the 10m by 12m billboard with that photo which I took a year earlier in Alicudi Island, where I used to live.

Where? Alicudi? No way, I had no idea!

Absolutely! For a period I lived in Alicudi all year round: summer, winter, all the time. I used to permanently live on Alicudi from 2000 to 2003 and while there I happened to take a picture of 2 ostriches on a boat and a picture of a donkey on a boat, which was the stronger one, and put it on display at the Biennale.

Speaking of that, I have another thing that I’m curious about: your work with animals. Tell me a bit about how it started.

I never had an affinity for animals. Never. But when I was living in Alicudi there was a co-inhabitant who had settled down there long before me, and he was trying to start breeding ostriches. He had two of them and he kept them in a large, fenced area near the sea. When I saw these ostriches in such a situation, out of this world, I imagined the picture of these two ostriches on the boat. And from there the great amount of work involving animals began, and even though I never had a great affinity for animals, we human beings have an ancestral bond with animals. After opening this door came the works with zebras, polar bears and so on.

And at a certain point a musical element was introduced in these works, or rather, the sound of their voices which then becomes music in your pieces.

Yes, the public artwork Grrr Jamming Squeak was the first time I used sound, I think, and it came to my mind for various reasons, from my life at that time in 2010. A couple of years prior I had just moved to Alaska adding another ingredient to the mix. In Alaska there was Monday Love as Love as in showing love on a Monday and it consisted of a friend [John Reeves] opening his house up to everyone to meet up and make some music, creating a situation of jamming and music.

Did you meet your husband there for the first time? Or had you already met him?

Yes, I didn’t meet him at that event, but he took me there. The day we met was a Monday at the airport. A mutual friend introduced us and then we went to this Monday Love. For years John opened up his home and set up a campfire in his garden, and he had a basement full of instruments. It was a social situation of inclusivity where even strangers could come, but it was a special moment in Anchorage where security and feeling safe allowed for such an extraordinary phenomenon to happen. We met up at 7 in the evening and anyone who showed up was welcome, and anyone who missed it could be there the next time.

Both musicians and non-musicians?

Non-musicians as well, like me after all. People from all paths of life and of all ages. Dogs were also welcome. Someone might bring some food and some drinks; it was a special situation. Obviously, this was a thing that fascinated me. It was a rare occurrence that it could happen in a community, and it was happening right there and lasted for years.

Beautiful. Truly beautiful

Until Anchorage changed, it expanded, and you couldn’t open your door to everyone anymore, but it lasted several years. Meanwhile, Karma and I made a trip to St. Paul Island, which is home to 500 thousand seals. Its population was made up of something like 30 people and 500 thousand seals.

Where exactly is St. Paul’s Island? In the Pacific Ocean?

It’s part of Alaska, there are two islands and they’re called the Pribilof Islands, St. Paul and St. George, and they are the place where all the seals from the Pacific go to reproduce. In the past millions of seals used to gather on these shores. Now only half a million, or at least that was when I went there. So Karma and I found ourselves looking at this stretch of land covered in seals being rowdy, just like a crowd of Italians, and Karma immediately started composing music with the seals and the sounds they made. From that episode I elaborated Grrr Jamming Squeak, a professional recording studio which, in those years, was still an extremely luxurious, rare, inaccessible and difficult place to experience, but soon after, the ‘home studios’ started growing in popularity. Today any kid can have a musical studio in his laptop if he wants, or at least something close to one.

Back then it wasn’t as easy. Electronic music required some rather complex equipment.

Indeed, and it was a studio with more than 20 available instruments, from a violin to the electric keyboard, as well as 100 different, royalty-free animal sounds. People could use this studio with a sound engineer and another person present to assist them just like in a professional studio, at everyone’s disposal. They could play music with a small caveat: in whatever they played, they had to include at least one of the animal sounds.

I remember it clearly because it’s there that I made my entrance, correct?

Exactly.

I entered the scene with a first thing. Both in Rotterdam and Saint Petersburg, and at that moment something seemed to be triggered. I’d like to ask you, was it a hidden passion or was it pure chance that you had an attraction for design items? They started off with a purely functional role but later somehow developed a certain strength in your exhibition in Saint Petersburg, where I was present. They seemed to influence the space they were in, along with the music and the performance.

I think you underestimated the role of those objects because my passion for design already existed. Being born in Milan made me absorb it. I just have it. When I created this studio, I designed its every detail. It included an area for the musicians, one for the sound engineer and the assistant, as well as 2 areas, designed in the most extraordinary way I could, that would host the audience. At this point, I don’t remember exactly how, probably after seeing your work on the internet, I tried contacting you.

It was something of the sort, one of those sparks like a quick call in the morning. This is what I remember: you told me something along the lines of “I really like what you do, I’d like to include your things in one of my upcoming pieces” and then we started talking about it. I offered the things I had available at the time because you were short on time. We agreed on the objects, which were originally made for a project with Patricia Urquiola, and that takes us to Rotterdam. In Saint Petersburg we made a more tailored collection of objects, exactly what you were looking for in terms of typology and volumes.

So, you say it was pure chance that although you had already made those pieces for others, they were perfect for me!

Absolutely! I remember showing them to you and said: “I have these things available immediately”, I might have sent you some pictures of them and you chose the ones you preferred which became part of your work in Rotterdam. There was a magical coincidence that is always needed in everything. At that point, thanks to your predisposition, your passion for design kindled. As you said, the place you were born matters and Milan is certainly the capital of this way of thinking without a doubt. Finally, we have arrived at the last matter of this interview: we might have a collaboration in the future to develop some ideas and projects, or even just a concept about something we can work on together in the realm of design. Something that involves a person within the art world who also loves design with an idea of what can become a hybrid object of sorts that retains its expressiveness beyond being a functional object.

Maybe we can. I’m not sure if this is going to be interesting enough for this interview or not but, I have done some pieces with miniatures of Vitra objects.

It’s true! So very, very true. The miniatures.

I got the entire collection and arranged it into sphere-lamp-sculptures. I also took photos depicting a naked female body from the back with one of the miniatures close to the buttocks. Also related to the world of design are the sofa miniatures I made, the last of which is the one that inspired you to make our big sofa: my miniature of the Andy Warhol sofa, the last in a series of 10 or 12 pieces. I made miniatures of iconic sofas, but not design sofas from a renowned designer, except for once when I made the exact replica of the Sacco armchair. All the other sofas were “a modern yellow sofa”, “a Paolina sofa” which, by the way, I called Paolina, but I don’t even remember why, but you understand which one I’m talking about though.

Sort of a French icon so to speak.

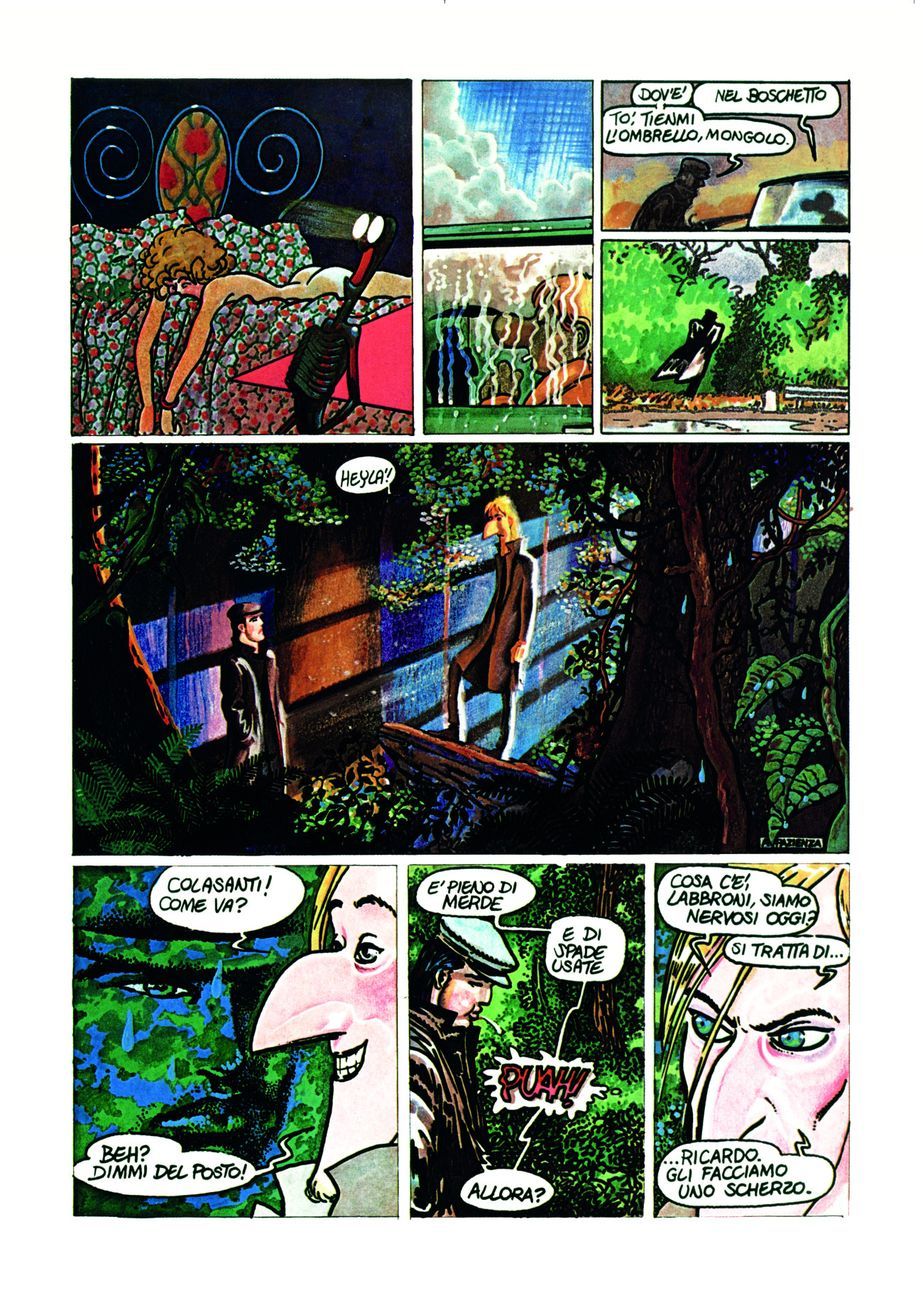

Zanardi, Lupi by Andrea Pazienza ©Marina Comandini Pazienza. Source: www.artribune.com

Precisely. Like a daybed. I also did “the blue 3-Seat family sofa”, “the sofa bed” as these figures of a concentrate, a condensed essence, a monad that represents all sofas of that type.

Unique in a way, a unicum.

I made it into a symbol of the modern sofa. I scaled them down, turned them into sculptures and soaked them in perfume until they would break apart. They break apart wet and mouldy, pieces break off, and I displayed them like that. By the time I worked with you, my relationship with design was already strong.

It’s strong, and that is exactly why we will do fantastic things together. Paola, I know your time is up and I’ll close the interview here. We will keep in touch of course. I can’t thank you enough. I learned many wonderful things in this conversation.

You are too kind.

Truly wonderful.

You know, it could have been one of your friends’ fault. I wouldn’t be surprised if you told me Andrea Pazienza was your friend.

He was my friend!

Because his comics showed me art for the first time.

No way! Andrea? Before moving back to Udine, I lived for 15 years in Bologna.

I thought he might have been your friend for that reason.

He was my friend indeed.

I knew you lived and studied in Bologna.

Not only that. My first husband was a comic artist, a close friend of Andrea’s. At the time Bologna was a wonderful, absurd, fast world, and Andrea was our neighbour. By the way, Igor [Igor Tuveri], my ex-husband, is in Milan with an important exhibition on Japanese artists at the PAC. He is the only non-Japanese artist, but he knows Japan very well. Andrea had issues you probably already know about, very serious ones. Often when a deadline was closing in for one of his works for Milano Libri, he found himself working the last night of the last day, as you can imagine. At that point, all his dearest friends went to his place to help him out because his work was due and he was incredibly late. That said, he was brilliant, unfortunately self-destructive, but with an immense and powerful soul. A special person.

source: www.artribune.com

His soul showed me art. Every now and then, back when I was studying engineering, I used to relax by copying Disney comics like the Lion King while at the library. One of my friends from Gallarate showed me Pazienza’s comics and I lost it. I completely lost it and said: “But this is nothing like the others! I mean, Disney is also art, but this is a concentrate!” I saw this thing and I had no idea what to call it. I saw it and he, Andrea Pazienza, dragged me out

What a coincidence, just incredible.

I swear! I got curious later and discovered Egon Schiele after Andrea Pazienza. It’s in many of my interviews, but few people understand like you do.

I completely understand. The thing about Andrea was that either you loved him or you hated him, but if you loved him he was able to captivate you. He truly had the soul of an artist, you know, to its fullest and thus without limits. Unfortunately, often exceedingly without limits. We all missed him dearly when he died. We all know that the stronger souls often have a short transit.

I surprised you, didn’t I?

I was not expecting it.

I just guessing that he might have been your friend. No one told me before.

That’s the surprising part.

And with this extraordinary coincidence…

We’ll say our goodbyes for today. Bye dear Paola!

Ciao and thank you!

Safe travels!

Creator

Paola Pivi

Paola Pivi was born in Milan in 1971. She lives and works in Anchorage, Alaska. One of the leading artists of the contemporary international scene, she blends the familiar and the alien in her work, often using widely recognised objects modified in scale, material or colour, and stimulating people to see things differently...

Past Exhibition

Paola Pivi: I Want It All

The Andy Warhol Museum

Unusual and unexpected situations arise when nature and its laws are played with. Being confronted with the bizarre and the curious, wondering whether it really is possible for such a thing to happen, is the norm when engaging with one of Paola Pivi’s works, from her installations to her photography.

117 Sandusky Street

15212

Pittsburgh, PA

22.4→ 15.8.2022